Ultimately, we have forgotten that time is needed for the water cycle.

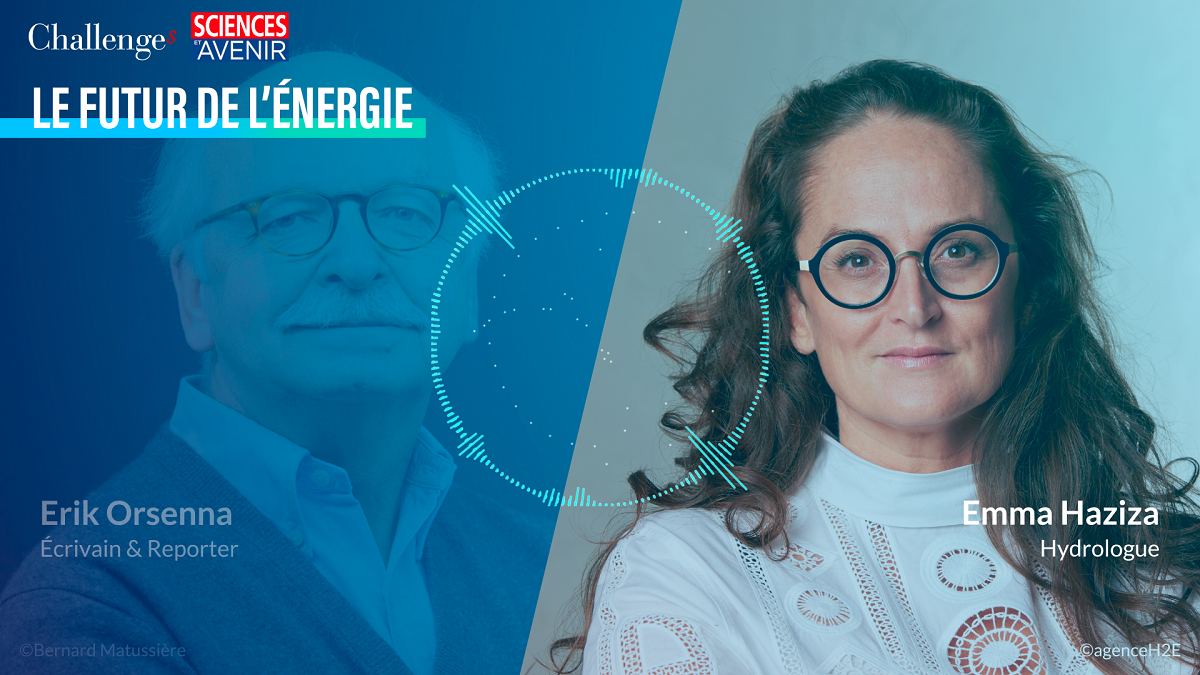

Erik Orsenna

Hello, Emma Haziza. You are a Doctor from the École des Mines in Paris and have created a centre for action and adaptation to climate transitions called Mayane. You have conducted a very specific analysis of a number of issues, in particular the issue of energy and the relationship between water and energy. It’s when we lack it that we realise that water is involved in everything. Is water also involved in energy?

Emma Haziza

Of course. We are becoming more and more aware that water is involved in our produce, our food and our clothes. But we are less aware of the fact that it is involved in almost all forms of energy. To extract oil, it is necessary to inject pure water ; for the extraction of coal large tanks of water are needed to separate out the good from the bad.

Erik Orsenna

Water separates the wheat and the chaff.

Emma Haziza

Let me give you an example. In 2021, there was a very severe drought in China, on the Pearl River, and at that time, they had to try to find new forms of energy because the main form of energy produced from water is from hydroelectric dams. But these were empty at the time. So China decided to convert very quickly to coal, except that there was not enough water to extract coal. This meant that China had to buy liquefied natural gas from large Qatari LNG producers.

So you can see how there is a link between all these forms of energy and that water is, ultimately, at the heart of it all.

Erik Orsenna

Consider what seems most obvious, namely hydroelectric power. As its name suggests, if there is no hydro, there is little electricity. How do you see the situation regarding water resources at the global level on the one hand and for France and Europe?

Emma Haziza

A recent study highlights the fact that just over 50% of our lakes, and in particular the surface water in these water bodies, has been lost, whether they are man-made or natural. So this water is tending to disappear, but what's interesting is that it's coming back to life in places where man is no longer present, on the Tibetan plains, on the Great African Rift. It's as if water is seeking refuge somewhere where it's protected, where it can't be touched, because in those places reserves are being replenished. However, we are losing our surface water. This surface water is mainly getting used because man has settled around it and therefore when it disapears man is forced to move as well. This study is quite interesting because it shows us all the changes that are taking place and that water is being reduced to nothing on a global scale.

Erik Orsenna

In France, I believe that hydro accounts for 10 to 12% of electricity. How do you see this developing for us in the next 10 to 20 years?

Emma Haziza

A bit like the Serre-Ponçon lake, which was very symbolic during the drought of 2022 in particular. This lake is above all a hydroelectric dam that normally supplies electricity. But it also represents all the water users and stakeholders surrounding it. On the one hand, there are the people who make their living from tourism. Downstream, there are the farmers and the cities that need to be supplied with drinking water. All these stakeholders are at the centre, with EDF unable to produce any energy. According to climate projections for the next 10 years, France is the fastest-warming country in the world, and we're really at a tipping point.

Erik Orsenna

France is the fastest warming country in the world?

Emma Haziza

Exactly. 20% faster than the rest of the world.

Erik Orsenna

In a book I wrote 15 years ago on the future of water, I was saying: "If one thing is clear, it's that drought issues will never affect our country, a temperate country if ever there was one.”

Emma Haziza

Well, maybe that's the problem. We used to be a country that was not only temperate, but rich in water, with many users. And it is precisely what makes this gap, this very powerful tipping point between being in a very comfortable situation and reaching a situation where we are moving towards the land becoming more arid so difficult.

Erik Orsenna

It's the spoiled child syndrome.

Emma Haziza

Right. And why is it so much more difficult than for countries that are used to chronic water stress and have taken the time to get used to it? We're not ready at all, we haven't changed our agricultural sectors at all, because the tipping point occurred within 5 years. And 5 years is too fast to be able to adapt on a human level.

And why is France particularly concerned? Because it is the Arctic that is warming the fastest in the world. So it involves North America and northern Europe. And in the middle of northern Europe, we have France, whose Atlantic coast usually receives humidity from depressions, brought by the prevailing winds. Except that we're changing the direction of the wind. By changing the direction of the wind, we are losing water, whereas we used to get more water. The water arriving in Brest used to provide water for Strasbourg. Now we're losing the water we have because we've lost the areas where we could conserve it. Wetlands, all those areas of ponds that have been drained to make way for farmland, are areas where small water cycles used to take place and no longer do.

This raises questions about our large dams. We saw the Loire in 2022 and the Rhône has always experienced climate extremes. In 1976, people were playing bowls in the river's major bed. However, we are no longer dealing with climate variability. We are seeing a trend towards snowfall rates that are going to start falling massively. So, necessarily, these rivers, which will receive less water, will give rise to what is happening in China and the major dams in Brazil, which ran dry in 2021 due to historic drought.

Erik Orsenna

So, in the energy mix, in terms of the contribution of different energy sources, you are very wary of having high expectations from dams. There is also the question, as we have seen when working on mining issues, of the materials for photovoltaic panels and wind turbines. Obviously, as in any industrial process, water is needed. If we no longer have direct water resources or fewer and fewer hydro resources how can we find less water-intensive sources of energy?

Emma Haziza

That's a crucial question. Take the example lithium and the Atacama desert. When you have a lot of oil or a lot of money, you get plenty of water. In this case, we are able to bring water to the coastal plain of Chile, bring it 1,500 kilometres inland, and bring it up to an altitude of 2,500 metres to supply desalinated water to the Atacama plains to extract lithium, because it's worth the effort.

In fact, we are able to transport water everywhere. Look at the Arab Emirates, we have entire territories that are not crossed by any river and that nevertheless desalinate on a massive scale, with the consequences that we are now aware of, be this the use of more than a dozen chemicals or high salinity, due to brine being discharged in the local area.

New solutions are emerging, and although they are still far off, they are interesting. What strikes me as a shame is the idea that this is the only solution. Whether it’s desalination or the reuse of waste water, there is something of a tendency to wave a magic wand and say: “96.6% of our water is in our oceans.” Or: “We have three times the equivalent of our oceans 700 kilometres underground”. This leads to people imagining all sorts of incredible things. There is indeed water, but available water is actually very scarce.

Erik Orsenna

And very expensive.

Emma Haziza

It is very scarce and very expensive, because it is fresh water. It is consumed on a massive scale all over the world. We are taking water from groundwater because it is the easiest fresh water to extract. You just have to drill everywhere, and that’s what has been done. Today, as NASA has shown us, over the last 20 years, there has been a change in Earth's gravity. So we realised that there are 19 tipping points in the world, where we have extracted all the groundwater. And in the Great American Plains, it would take 2,500 years of rain to restore this groundwater.

So we are currently at a tipping point and we will need to find solutions. One solution that may be interesting is osmosis. Osmotic energy is an interesting solution that has so far been too little explored.

Erik Orsenna

Let’s say a few words about osmotic energy. I visited one of the laboratories of the Compagnie Nationale du Rhône, CACO, where this mechanism is still at the laboratory stage. Could you tell us what osmotic energy is? I see it as a kind of allegory for a love affair, sort of love at first sight, because it basically concerns the link between fresh and salt water.

Emma Haziza

Exactly. Energy is produced by the salinity differential.

Erik Orsenna

That is, energy comes from difference.

Emma Haziza

From two different water forms meeting.

Erik Orsenna

And making use of that difference. It's really quite amazing.

Emma Haziza

Exactly, yes. And these water forms come together to produce energy. It's interesting because when you look at all the water in the world, you clearly see that bodies of water don't mix. The oceans meet, but they don’t mix. You can see when you go to Cape Town, South Africa, how much these oceans keep themselves separate from each other.

Erik Orsenna

Also, the Amazon. I have been to Manaus several times where the Rio Negro and the Rio Solimões flow alongside each other. Here too, using the allegory of love, they know that they are going to merge, but they are slow to admit it.

Emma Haziza

This capacity seems interesting because there are no negative external factors, which is the case today with desalination or the re-use of waste water, which must be thought through and considered only in certain cases. We still have plenty of other solutions. In particular, I'm a great believer in recovering water vapour and condensing it for local use.

Erik Orsenna

One thing all our listeners need to be aware of is the magic of differences in water states. There is liquid water, there is water as vapour, there is water as ice, there is water as snow, etc. Water is able to change form, in this change of form, energy is released. As a writer, I'm also looking for these great similarities between water processes and energy processes. Because water, energy and life are all one and the same.

Emma Haziza

It changes state and it changes place. That's what's happening today on a global scale, and this dance is taking place thanks to the sun, which is tending to get stronger.

Erik Orsenna

It's beautiful what you say. In other words, it's the dance of the sun.

Emma Haziza

It's the dance of water which, sooner or later, bubbles up again. And I believe that water is in the process of tuning into the world. That is, the water cycle is accelerating and our world is accelerating.

Erik Orsenna

Water sets the tone.

Emma Haziza

Exactly. Our world is accelerating. I think there is something quite scary about the fact that we want everything to go faster and faster in our world. Everything has to run straight, our waterways must go faster to where they have to go. Ultimately, we have forgotten that time is needed for the water cycle. Water that moves from one reservoir to another will never stay in the same place for the same length of time. Sometimes it will stay for thousands of years in one place, then a few weeks in another, and then it will return to the atmosphere for a few hours. Except that at a higher temperature, we accelerate the time it takes to condense or fall as precipitation, ever more drastically. We saw it recently with the floods in Italy and elsewhere.

Never confuse speed with haste is what I was told that when I was little. In fact, rain falls to the ground and it can’t find its way underground. Normally everything is regulated by the land, which acts like a sponge. But with machinery over-compacting the soil for agricultural purposes, and with urbanisation creating artificial surfaces, water can't find its way underground. When it finds its way underground, it has time to rest, it has time to enrich itself, which is why we have mineral water. It then has time to find its way back to its source and be reborn. We don't give it that space any more. It's as if we'd closed off a reservoir and extracted this fossil water that has accumulated over millions of years. We're extracting water that has taken its time, and what we want to do is save time.

Everything is in reverse. However, if we manage to transform this cycle and take our time, the sources are reborn and reawaken.

Erik Orsenna

If the soil is poor, dry or dead, water won't find its way into the soil. As a proportion of land use, we have created artificial soils in France just as much as we have destroyed the Amazon rainforest. In other words, in a way, as you rightly say, we have deprived water of the places where it is able to reside. And people say: "We're going to conserve it," except that it doesn't penetrate into the ground.

Emma Haziza

Yesterday, I heard a hydrologist say: "Ultimately, there's no difference between water that evaporates from a maize field and water that evaporates from a tree. And somehow, the tree uses too much water, so it's a problem.” It's not the first time I've heard this, and it's incredible because if you only look at one side of the picture, you only get one side of the truth. When a tree draws in 1,000 litres of water, transpires this water, which then generates water vapour, accompanied by pollen and everything else it emits, it nucleates the drop of water and then recreates the rain. It's clear that we absolutely must respect this fact.

And what we forget is that we're not the only users of water, the whole world, all living things need water. So every time we decide to divert a river, the whole biome collapses. We have the feeling that we are only going to be supplied through pipes in this world and that the only alternative we have is our energy capacity for ever increasing production. The fundamental question is ultimately: what do we want, what do we desire? You only eat three times a day, but at the end of the day we always want more. But still more for what?

We don't ask ourselves this question any more, and I see that we are in the process of tipping over into a world that is becoming unhappy because it no longer takes the time to think about its real needs and what is essential for it. When we rediscover these essentials there can be renewal. I've just come back from Colombia, where I spent three weeks with the Kogi people, and the only thing we did was laugh, eat and talk for 6 hours. That's what it's all about.

Erik Orsenna

And what is their world-view, in a nutshell? The big difference from us is time, they take their time.

Emma Haziza

And they are not disconnected from the earth. In other words, they are a logical continuation of their territory. They have links, which means that their territory is a bit like acupuncture points, sacred spaces that need to be protected, that need to be preserved and each element finds its meaning. I was able to see an area where there were wastelands caused by intensive farming and intensive coffee-growing operations. The land was acquired by a French association that helped them recover ancestral land stolen from them. In 6 years, I have seen everything transform. I saw the photos from before, all the studies that had been done. What's amazing is that I've seen the springs come back to life. Why is that? Because they celebrate the frog, because they celebrate each element having its place. We have forgotten that we were ourselves are part of a system.

Erik Orsenna

That's exactly the battle we're going to fight to restore the Guinean Fouta-Djalon massif, from which the biggest rivers in West Africa flow. In other words, the River Senegal, the River Gambia and, above all, the River Niger, to save what are known as the headwaters of springs - a phrase I'm very fond of.

Emma Haziza

They told us: "You know, the mountains talk to each other. "We asked them how they communicate. They told us: “They communicate through the clouds, of course. A cloud passes over a mountain, picks up information and transmits it to the mountain next to it.

Erik Orsenna

That's exactly what we saw with the trees, that they talked to each other.

Emma Haziza

Exactly.

Erik Orsenna

That's exactly what happens with the connections between fungi, bacteria and roots.

Emma Haziza

Yes, all that balance.

Erik Orsenna

In other words, listen carefully, they're talking to each other. We’re not the only ones who can speak.

Emma Haziza

Something even more incredible, they tell us that a river is a book, an open book that tells us a story. And every day they go to the water's edge, they draw water and they read what the river tells them.

Erik Orsenna

This is exactly what we are going to do, since we are going to have 200 to 300 metres of river adopted by 4th and 5th grade classes. So, at the same time as they learn to read, just delete a consonant and we go from tree to free and progress like that.

Emma Haziza

We need to regain our freedom, we need to regain our power. And above all, children need to reconnect to the territory in which they live. They don't even know there's a river close by. They think it's a path, but we need to explain and allow them to read the landscapes. They read things on their mobile phone every day, but at some point, if you don't return to your source, you forget.

Erik Orsenna

So you can see that the questions raised by energy obviously involve technical data, osmosis, recycling, etc. Reserves can be found at certain times depending on geological factors. But there's much more to it than that, and we can see the extent to which water is not just a material, but a mirror for our civilisation. I understand that on your trip you were with a renowned mathematician, Cédric Villani, who happens to be a close friend who we have projects with.

Emma Haziza

Exactly.

Erik Orsenna

At the most abstract level of science, mathematics, the most detached from human existence, what is someone like Cédric looking for in this remote tribe?

Emma Haziza

What was fantastic was that Cédric brought us a different perspective, he raised questions that we weren't asking ourselves. He complemented us as part of a multidisciplinary team of six scientists. Each came with their own concepts, their own history - two great naturalists, a physicist, an anthropologist - and they all tried to forge a dialogue. Saying: “We don’t know each other, let’s get to know each other, let’s get to talk at last. -

The Kogi people are the last pre-Columbian society in the valley of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, an incredible mountain that rises to an altitude of 5,775 metres, 42 kilometres from the sea. In other words, the more you climb, the more you see the sea, it's absolutely magnificent. These exceptional landscapes are losing their water as they lose their snow. And the Kogi tell us that snow is the memory of a mountain, if we lose the snow, we lose its history.

Erik Orsenna

And its language. In other words, the mountain will no longer be able to speak.

Emma Haziza

Exactly. And they said to us: “We are in such a serious situation that we need to start communicating with each other”. For Cédric and the others, it made us all uneasy. We were all overcome by what it means to be human. We are made of water ourselves, our brains are made of water, we could not talk if we didn’t have all this water within us. They looked at us and said: “Why did you touch the underground water? You should have left it alone. You had the springs, you had the rivers. Why did you take this water from a place where it was protected? In fact, they think so much about preservation, because they are part of this land. While we are completely disconnected. Reconnection is therefore essential if we want to have a sustainable, liveable future. But what is exceptional is that nature is resilient, it is reborn, it springs up again wherever it is allowed to breathe.

Erik Orsenna

Summing up these extraordinarily significant remarks, I am struck by two points. The first is all the ties we have severed. We have done everything we can to separate ourselves, on the one hand, and on the other to accelerate. So, in terms of space, we're fragmented and, what's more, we're accelerated.

Emma Haziza

I think that in wanting to separate, we thought we were becoming more powerful. But in fact, we lost our power at that point, because we connected to other things. We have spent all these past decades being hacked by neuromarketing, which tells us exactly how we should live, what we should buy, what is good for us to be happy and we have forgotten to ask ourselves what makes us happy. It's something that goes way beyond the issue of water, but is a reflection of our societies. And water is in a bad way all over the planet because our society is in a bad way.

Erik Orsenna

It's a mirror.

Emma Haziza

And where water is in a good state, we are happy.

Erik Orsenna

And people say: "I have a bad back," but they could also say, "I have bad water”. -

Emma Haziza

Exactly. And I think something is very wrong with my water and it's time we got it back to a healthy state.

Erik Orsenna

Thank you, Emma

Emma Haziza

Thank you, Erik.

Emma Haziza is a researcher-entrepreneur serving the massification of adaptation to climate change. Columnist on France Info, inspiring speaker, Emma founded her own action research structure Mayane Resilience Center and is currently continuing her action through the development of a start-up Mayane Labs. She also chairs the Mayane Education association to raise children's awareness of life-saving actions in flood-prone valleys, water savings and the local impact of climate change.

Doctor of the Ecole des Mines de Paris and a scientist recognized for her educational qualities and her capacity for action, she intervenes within scientific committees (UNICEF, France Ville Durable, Ministry of the Civil Service, etc.) and councils of administration (Eau de Paris).

Sign up for the ENGIE Innovation Newsletter